There was no forest.

No orchids. No birdsong.

Just dryness. Exhaustion.

No one looked at this place and saw the slightest potential.

No one, that is, except José Koechlin.

As we celebrate our 50th anniversary, we continue to reflect on the milestones that have shaped our journey. In this third chapter, we look back at how a once-eroded landscape in Machu Picchu Pueblo was reborn as one of the planet’s most biodiverse ecosystems.

But to understand how it all began, we need to go back a little further…

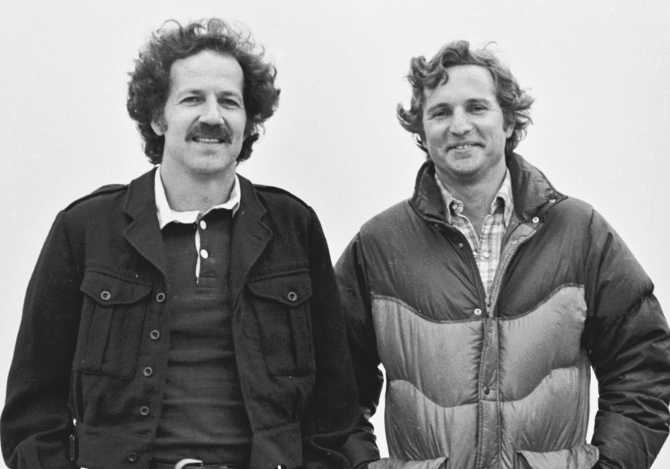

In 1972, José Koechlin co-produced Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Werner Herzog’s iconic film. While audiences were captivated by the landscapes on screen, José was already imagining how to protect it. Three years later, that vision took root: Inkaterra was born—along with its first property, Cusco Amazónico.

And now, back to the place that brings us here today…

Where the Inkaterra Machu Picchu Pueblo Hotel now stands, there once was no forest. Just arid land used for tea production and grazing. It was not the kind of place anyone would choose to build a hotel. No one—except José Koechlin.

A nature lover at heart, he arrived in the 1970s with an unconventional idea: instead of building first, let nature return.

He dreamed of a forest. And waited.

For fifteen years, native trees were planted. The soil was restored. Birds returned. The cock-of-the-rock. Butterflies. Orchids. Slowly, life came back.

Only then, in 1991, did the hotel open its doors—starting with 15 Andean casitas, thoughtfully designed to blend into the landscape. Today, there are 83, surrounded by gardens, waterfalls, and forest trails. A hidden refuge in the heart of the cloud forest.

Walking through Inkaterra Machu Picchu Pueblo Hotel feels more like exploring a nature sanctuary. Across its five hectares live 311 species of birds, 372 native orchids, 98 types of ferns—and a historic tea plantation, restored and now producing one of the world’s finest teas, recognized at the AVPA Awards in Paris.

This is more than a hotel. It’s a living story.

A place that wasn’t merely built. A place that was allowed to grow.