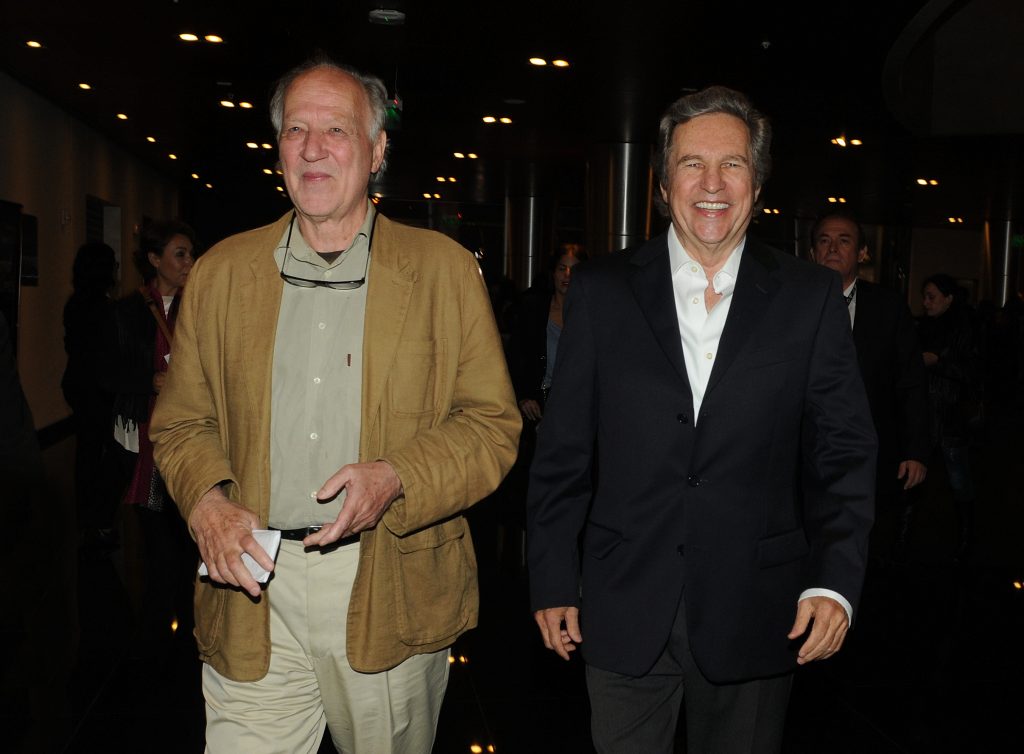

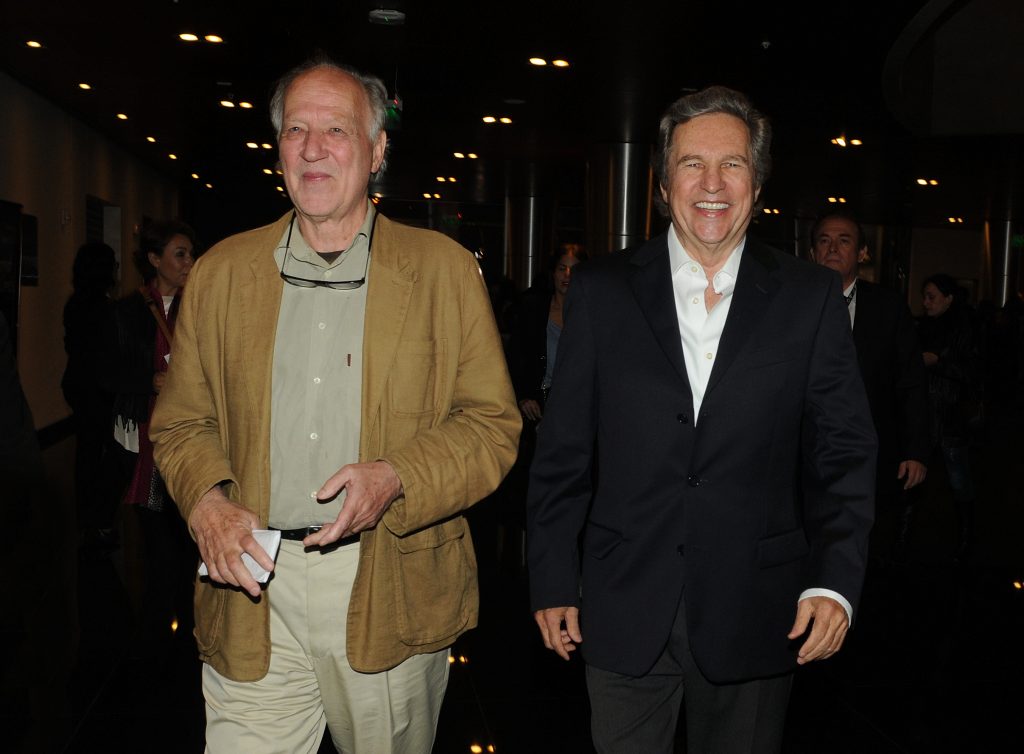

Werner and I met by the end of 1971, when he arrived to Lima to present his first films at Champagnat High School. By that time he had created experimental and profound works such as Even the Dwarfs Started Small and Fata Morgana, aiming to grasp the unfathomable aspects of human existence. Werner had received a grant from a German TV station to make a film on Lope de Aguirre, the mad Conquistador that betrayed the Spanish Royal Crown and led an expedition in search of El Dorado.

After attending the screenings and starting our friendship, I convinced him to reach a wider audience with his first feature film. My role as co-producer was decided with a verbal agreement and a hand shake – no budget, no paperwork nor any form of restriction, in order to let Werner work with complete freedom. Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)1 was released a year later and it played in Parisian theaters for three years in a row, contributing to the development of tourism in Peru. Nowadays it is considered one of the best films of all time.

For me, cinema is the most effective way to present a destination. It occurred with Acapulco during the 1960’s, when it was promoted by film as a paradisiacal beach. Tourism in many other destinations in Europe was encouraged this way. Making Aguirre helped portraying the true character of Machu Picchu, particularly with the arresting take that opens the film, in which Incas and Conquistadores descend like a row of ants from the cloudy heights of Wayna Picchu Mountain, before immersing themselves into those “fever dreams” concealed in the Peruvian Amazon.

In 1978, aiming to recover the investment for Aguirre, I travelled to Germany to meet with Werner and proposed him to produce another feature film in the jungle. I told him about Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald, Peru’s great geographic hero. Fitzcarrald was the first to cross through the ‘Fitzcarrald Isthmus’. He integrated Madre de Dios to the Peruvian economy with the Amazon Rubber Boom, and defended the country from foreign migrants. He deserved a 20th Century monument, a film to show his determination.

One detail of this story fascinated Werner, as he recalls in the foreword for his book Conquest of the Useless: “A vision had seized hold of me, like the demented fury of a hound that has sunk its teeth into the leg of a deer carcass and is shaking and tugging at the downed game so frantically that the hunter gives up trying to calm him. It was the vision of a large steamship scaling a hill under its own steam, working its way up a steep slope in the jungle.” Werner intertwined this epic image with the story of an opera fanatic determined to bring Caruso to the Amazon, and to avoid any contingencies with name rights we named it Fitzcarraldo (1982)2.

Making Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo were true adventures and unrepeatable achievements. Both were filmed in extremely harsh conditions in the rainforest, I believe no other film will be made under those circumstances. Werner and I faced limit situations and, under these conditions, both of us became more resilient towards adversity. Experience taught us that there is always an alternate way of working, living and solving problems to get through. There were very difficult moments that served us for becoming true friends.

Fitzcarraldo is one of the main modern-day ethnographic documents, which presents Maschos, Piros, Campas, Aguarunas and other native communities. Their participation is documented by other film I produced, Burden of Dreams (1982)3, Les Blank’s documentary on the four-year making of Fitzcarraldo. It depicts the conditions endured by local communities to protect their land, cultures and traditions from foreign influence.

We initially met with Mario Vargas Llosa and proposed him to write the screenplay for Fitzcarraldo, but he was still writing The War of the End of the World. Jack Nicholson was the first choice to play ‘Fitzcarraldo’. After joining Werner in the making of Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), we visited Nicholson in the set where he was filming Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Due to schedules, Jason Robards was casted as the main character and Mick Jagger in the role of Wilbur. Robards did not endure the virgin rainforest and left the production due to an illness. Mick stayed many days in the Lima Country Club Hotel, waiting for the produñction to start again. He was already committed to a world tour and he was not able to continue filming. Under these state of affairs the legendary Klaus Kinski got the lead role, while Claudia Cardinale played his paramour Molly.

Werner never had health problems while shooting, as he is a strong and knowledgeable soldier. He made a lot of research before working in Peru, as he always does for pre-production. He is blessed with the virtue of envisioning authenticity in people and environments, allowing true life to enter his films. He has a very strong will and does not accept any adverse situation to stop his work.

We frequently feed our friendship. After completing Fitzcarraldo, Werner has returned to Peru on many occasions. In front of a raging river in Machu Picchu he filmed some scenes for My Best Fiend (1999), an intimate portrait of his relationship with the unpredictable Klaus Kinski. He has also made Wings of Hope (2000), revisiting with survivor Juliane Koepcke the LANSA 508 plane crash, which Werner almost boarded during the making of Aguirre; and My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? (2010), starring Michael Shannon in an existential search with unexpected consequences. In 2018, Werner led 48 young filmmakers from 28 different countries in a two-week creative workshop at Inkaterra Guides Field Station, our most recent property in the Amazon rainforest of Madre de Dios. Guiding them from the spark to the editing, it was one of the most fascinating experiences ever for Werner, for his alumni, for the entire Inkaterra family, and for the Madre de Dios community.

Werner is one of the true artists of the 20th Century: many years ago Truffaut named him “the most important film director alive” and I believe he still is. The experience of producing Aguirre led me in 1975 to the foundation of Inkaterra Reserva Amazonica (Madre de Dios), which would soon become Peru’s first land concession with tourism purposes. Since then we have pursued our dreams with Inkaterra, producing scientific research to determine how to conserve biodiversity via ecotourism and sustainable development, pursuing the wellbeing local communities.